‘That day was my birthday, I was born renewed’

By Lily Combs

Baba Jan Saighani is one of the 6,022 refugees who entered Arizona last year.

I visited Saighani and his family for the first time in February. As I sat down at his dining room table with my mother, a teacher at his children’s school, he turned to his second eldest child and exclaimed something in Dari, his native language. He lifted his hands in front of him with a big, toothy grin as he talked.

“My dad says he can’t believe Americans are in his home,” Muzhda Saighani, his 15-year-old daughter, told us, her father nodding and smiling as she translated.

Saighani, a father of three daughters and three sons, is from Afghanistan. He was in Afghanistan when the Taliban first invaded in the 1990s, and he was there when they came again two and a half years ago.

His daughters were among the millions of girls in the country denied access to education by the Taliban regime, and his wife was among the millions of women denied the right to work when the school she managed was forced to close.

Before our official interview, Saighani insisted we share a meal together as is customary in their culture, so we ate a lunch prepared by his wife, Zakia Hashimi.

While we dined on a vibrant arrangement of chicken, rice and fresh vegetables and fruits — a traditional Afghan meal — our conversation centered around career paths for his daughters. Muzhda and his oldest daughter, Hadia Saighani, went back and forth asking about schooling lengths for different professions, from doctor to nurse, lawyer and even journalist.

The girls expressed interest in all of these fields, but ultimately, both want to pursue whichever profession they can start the soonest and still make enough to provide for their family.

“I have interest for law to be like my dad,” Muzhda told me. “But right now, I choose the doctor because I want to be able to help my family as soon as possible.”

After lunch, we moved to the living room for Saighani’s interview. We sat down on their two couches, me beside my mother, Saighani beside his wife and his three daughters forming a complete circle around us. He then began to describe life in Afghanistan while Muzhda translated.

“In Afghanistan, the woman cannot say anything,” Saighani said. “Everything which men say for the woman then the woman has to do that work. They don't have any rights in Afghanistan.”

As Saighani talked, he leaned forward and dried tears from his eyes. He proceeded to tell me how he witnessed girls arrive at school only to get slapped by Taliban soldiers and sent home. He said 15-year-old girls would be forcibly married to 50-year-old soldiers, a fate that may have been his daughters’ had they not fled, and that women in Afghanistan are controlled in every aspect of life by men.

“I cry because I could help the Afghanistan, but the Taliban wouldn’t let me,” Saighani said.

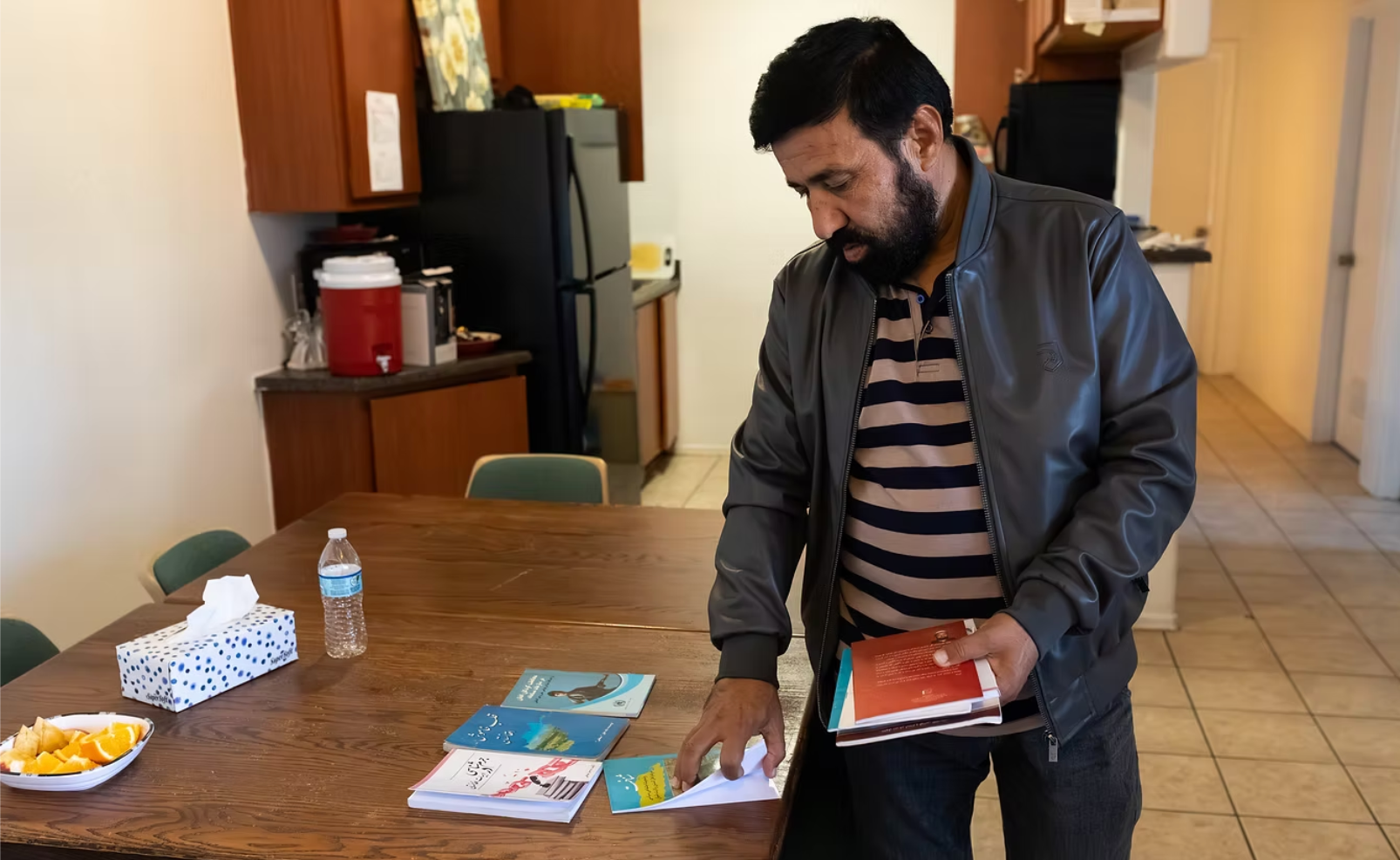

Saighani was born and raised in Afghanistan. He has worked in various professions throughout his life, including lawyer, judge and university professor, but the most important position to him has been that of a writer.

With 11 published books and his work as an activist for women and children’s rights, Saighani said he is well-known in his home country. His books are distributed across the provinces of Afghanistan, and he has spoken several times on national and international television against the human rights violations of the Taliban.

The Taliban is an Islamic fundamentalist group that first held power in Afghanistan in the late ’90s. It is commonly known for its Islamic-extremist views and violations of women’s rights.

A woman in Afghanistan is like a bird in a cage."

In 2001, the Taliban was driven out of power by United States-led forces after refusing to give up the al-Qaeda leader responsible for the 9/11 attacks. Nineteen years later, in 2020, the U.S. signed a peace agreement with the Taliban and began withdrawing its troops from the country. However, shortly after the last troops departed in August 2021, the Islamic fundamentalist group overthrew the new government and retook control of the country.

Under the Taliban’s regime, freedom of speech and the press are heavily restricted, public floggings are carried out based on violation of the Taliban’s interpretation of Islamic law and five public executions have occurred since it seized control in 2021. Women are restricted from working, cannot travel outside of their homes without a male chaperone and are required to wear full-body veils in public that reveal only their eyes. Additionally, women and girls are banned from education above primary school, which ends at 11 years of age.

“A woman in Afghanistan is like a bird in a cage,” Hashimi said.

Saighani spoke out against the Taliban, but with his family’s safety endangered by the group’s violent tactics, they were forced to flee across the Pakistan border four months after the second invasion.

“I couldn't live with someone who killed people because of their religion and who are not enlightened,” Saighani said. “I couldn't live, so that’s why I left.”

His family stayed in Pakistan as they sought permanent refuge in another country. There, all his children could attend school, and his two eldest daughters learned English.

Pakistan, however, was a haven for only a short time. As more Afghans fled across the border, police became violent toward the refugees and threatened to send them back to Afghanistan. While there, Saighani, his six kids and his wife were living off their savings, struggling to eat and with no opportunity to work. They received some cash support from two international human rights organizations: Amnesty International and Front Line Defenders. Nevertheless, life in Pakistan was still painful, Saighani said.

“I just wanted to be safe somewhere, even if it's a mountain or anywhere,” Saighani said. “I just wanted to be safe and not be killed.”

The path to resettlement is not always easy. The average time from referral to resettlement in the U.S. is two years. Some refugees, however, wait years or even decades more before they are granted resettlement. For most years, less than one percent of the world’s refugee population is resettled, according to UNHCR.

The resettlement process to the U.S. starts with UNHCR identifying vulnerable refugee cases to be referred. Cases are considered vulnerable if they fit into one of three categories: survivors of violence or torture, those in need of physical protection and women and girls at risk.

After a case is referred to the U.S., the individual or family goes through an in-depth screening and vetting process, generally taking 18 to 24 months, before they can be allowed admittance into the country.

Saighani and his family waited 20 months before they were approved for resettlement. After living a year and eight months in Pakistan, his hope for safety was finally fulfilled when he received news that his family would be going to the U.S.

“That day was my birthday,” Saighani said. “I was born renewed.”

Saighani and his family now live in central Arizona. He and his wife are learning English while their children attend school.

His two oldest daughters, who are 15 and 17, are working to complete all four years of high school in one year so they can go to college sooner to provide for their family. They hope to be finished in January next year, and according to Muzhda, they study all day every day to accomplish this goal.

“I know that my daughters will be the heroes of America,” Saighani declared.

Gaining refuge in the U.S. has provided Saighani’s family with the safety and freedom that was stripped from them in Afghanistan, but it has not fully freed him from the terrors of the Taliban.

I just wanted to be safe and not be killed."

Every day, Saighani sees Facebook posts about violence and human rights violations from friends who remain in Afghanistan. With family still in the country, Saighani is restricted from participating in activism for fear they might be killed. However, once his family is safe, he said he wants to speak out again. His primary way of accomplishing this will be through writing.

Between taking care of his family and working as a school janitor, the Afghan writer has several books in the making.

Saighani desires to use his books to expose the truth about the Taliban and enlighten his people. Some of his in-progress works include “The Jail of Women,” referring to the oppression women face in Afghanistan, and “Talking Animals,” about how animals act more civilly than humans.

His biggest desire, though, is to write a book encompassing all that is happening in his home country.

“If I find some supporter here that supports me [a] little, then I have to write everything which is going on in Afghanistan, which will be a very big book,” Saighani said.

Saighani has a long road ahead as he balances his writing, providing for his family and learning English, but he is grateful for all the opportunities he has in the safety of the U.S.

“Every day I go outside and I get a deep breath,” Saighani said, demonstrating with an audible inhale and exhale. “I am so happy that I am here.”

A letter to Americans

— Written by Baba Jan Saighani

I thank you because you helped me. You worked and paid taxes, and with your tax money, the American government was able to save me from the threat of death and bring me here.

You put your extra household items next to this garbage can. And several times I got household items from this garbage for free and took them to my house and solved my problem. While you don’t know that you helped me unintentionally, I am writing right now on the desk I got from your help.

I am indebted to you, and I hope that I can serve here in the future and repay your services.

Post a comment