Voices of the refugees in Arizona

By Lily Combs

Over one hundred and ten million — that is the number of people forcibly displaced in the world right now. One hundred and ten million people who have fled their homes for safety or are denied nationality due to persecution, conflict, violence, human rights violations or events disturbing public order. Of them, 40% are children.

This is the highest number of displacements ever recorded, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees’ (UNHCR) 2023 mid-year report.

Ninety percent of displacements as of June 2023 came from conflicts and humanitarian situations in Afghanistan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Myanmar, Somalia, Sudan, Ukraine and Latin American and Caribbean countries. With the recent Israel-Hamas war, 1.9 million civilians from Gaza are also estimated to have been displaced as of January 6.

110,000,000 displaced

Displacement takes different forms. Some people are internally displaced — forced to leave their homes but remain in their country — while others must seek refuge outside of their country’s borders. Refugees are the latter, those who have fled their country to escape persecution, violence or human rights violations.

There are currently over 36.4 million refugees, a number that has been increasing yearly. The UNHCR estimated that 2.4 million of these refugees will need resettlement in 2024. Resettlement is the process of a refugee voluntarily being relocated from their asylum country to a third state that has promised to grant them safety and put them on a path to permanent residency.

While resettlement provides life-saving protection, the path is often long and harrowing. Many refugees leave family and friends who remain in danger, wait years before resettling and deal with the difficulties of adjusting to a new language and culture while working to provide for themselves and their family.

In the last four decades, 103,802 refugees from over 100 countries have resettled in Arizona — 103,802 individuals, each with a unique story to tell.

‘That day was my birthday, I was born renewed’

Baba Jan Saighani is one of the 6,022 refugees who entered Arizona last year.

I visited Saighani and his family for the first time in February. As I sat down at his dining room table with my mother, a teacher at his children’s school, he turned to his second eldest child and exclaimed something in Dari, his native language. He lifted his hands in front of him with a big, toothy grin as he talked.

“My dad says he can’t believe Americans are in his home,” Muzhda Saighani, his 15-year-old daughter, told us, her father nodding and smiling as she translated.

Saighani, a father of three daughters and three sons, is from Afghanistan. He was in Afghanistan when the Taliban first invaded in the 1990s, and he was there when they came again two and a half years ago.

His daughters were among the millions of girls in the country denied access to education by the Taliban regime, and his wife was among the millions of women denied the right to work when the school she managed was forced to close.

Before our official interview, Saighani insisted we share a meal together as is customary in their culture, so we ate a lunch prepared by his wife, Zakia Hashimi.

While we dined on a vibrant arrangement of chicken, rice and fresh vegetables and fruits — a traditional Afghan meal — our conversation centered around career paths for his daughters. Muzhda and his oldest daughter, Hadia Saighani, went back and forth asking about schooling lengths for different professions, from doctor to nurse, lawyer and even journalist.

The girls expressed interest in all of these fields, but ultimately, both want to pursue whichever profession they can start the soonest and still make enough to provide for their family.

“I have interest for law to be like my dad,” Muzhda told me. “But right now, I choose the doctor because I want to be able to help my family as soon as possible.”

After lunch, we moved to the living room for Saighani’s interview. We sat down on their two couches, me beside my mother, Saighani beside his wife and his three daughters forming a complete circle around us. He then began to describe life in Afghanistan while Muzhda translated.

“In Afghanistan, the woman cannot say anything,” Saighani said. “Everything which men say for the woman then the woman has to do that work. They don't have any rights in Afghanistan.”

As Saighani talked, he leaned forward and dried tears from his eyes. He proceeded to tell me how he witnessed girls arrive at school only to get slapped by Taliban soldiers and sent home. He said 15-year-old girls would be forcibly married to 50-year-old soldiers, a fate that may have been his daughters’ had they not fled, and that women in Afghanistan are controlled in every aspect of life by men.

“I cry because I could help the Afghanistan, but the Taliban wouldn’t let me,” Saighani said.

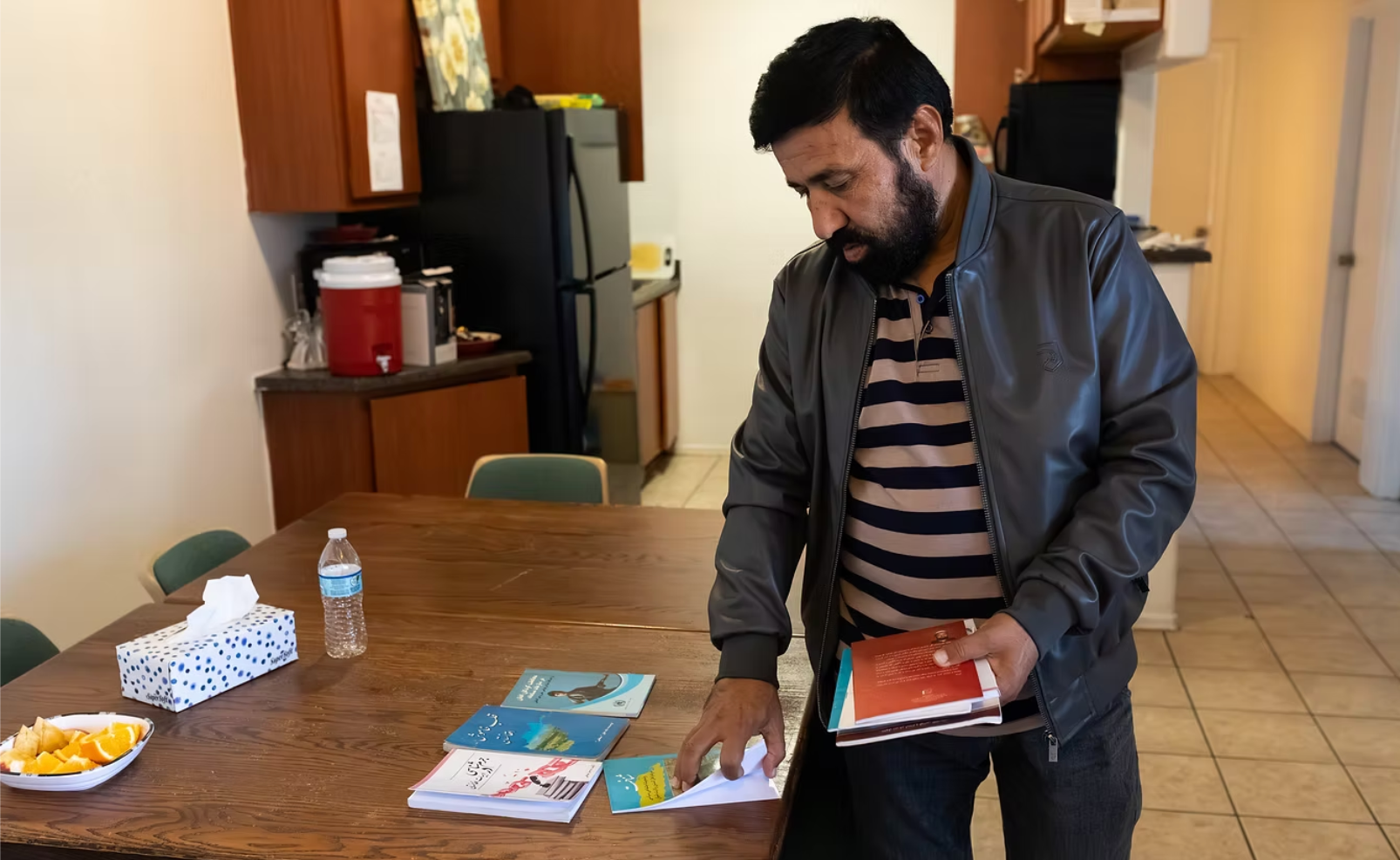

Saighani was born and raised in Afghanistan. He has worked in various professions throughout his life, including lawyer, judge and university professor, but the most important position to him has been that of a writer.

With 11 published books and his work as an activist for women and children’s rights, Saighani said he is well-known in his home country. His books are distributed across the provinces of Afghanistan, and he has spoken several times on national and international television against the human rights violations of the Taliban.

The Taliban is an Islamic fundamentalist group that first held power in Afghanistan in the late ’90s. It is commonly known for its Islamic-extremist views and violations of women’s rights.

A woman in Afghanistan is like a bird in a cage."

In 2001, the Taliban was driven out of power by United States-led forces after refusing to give up the al-Qaeda leader responsible for the 9/11 attacks. Nineteen years later, in 2020, the U.S. signed a peace agreement with the Taliban and began withdrawing its troops from the country. However, shortly after the last troops departed in August 2021, the Islamic fundamentalist group overthrew the new government and retook control of the country.

Under the Taliban’s regime, freedom of speech and the press are heavily restricted, public floggings are carried out based on violation of the Taliban’s interpretation of Islamic law and five public executions have occurred since it seized control in 2021. Women are restricted from working, cannot travel outside of their homes without a male chaperone and are required to wear full-body veils in public that reveal only their eyes. Additionally, women and girls are banned from education above primary school, which ends at 11 years of age.

“A woman in Afghanistan is like a bird in a cage,” Hashimi said.

Saighani spoke out against the Taliban, but with his family’s safety endangered by the group’s violent tactics, they were forced to flee across the Pakistan border four months after the second invasion.

“I couldn't live with someone who killed people because of their religion and who are not enlightened,” Saighani said. “I couldn't live, so that’s why I left.”

His family stayed in Pakistan as they sought permanent refuge in another country. There, all his children could attend school, and his two eldest daughters learned English.

Pakistan, however, was a haven for only a short time. As more Afghans fled across the border, police became violent toward the refugees and threatened to send them back to Afghanistan. While there, Saighani, his six kids and his wife were living off their savings, struggling to eat and with no opportunity to work. They received some cash support from two international human rights organizations: Amnesty International and Front Line Defenders. Nevertheless, life in Pakistan was still painful, Saighani said.

“I just wanted to be safe somewhere, even if it's a mountain or anywhere,” Saighani said. “I just wanted to be safe and not be killed.”

The path to resettlement is not always easy. The average time from referral to resettlement in the U.S. is two years. Some refugees, however, wait years or even decades more before they are granted resettlement. For most years, less than one percent of the world’s refugee population is resettled, according to UNHCR.

The resettlement process to the U.S. starts with UNHCR identifying vulnerable refugee cases to be referred. Cases are considered vulnerable if they fit into one of three categories: survivors of violence or torture, those in need of physical protection and women and girls at risk.

After a case is referred to the U.S., the individual or family goes through an in-depth screening and vetting process, generally taking 18 to 24 months, before they can be allowed admittance into the country.

Saighani and his family waited 20 months before they were approved for resettlement. After living a year and eight months in Pakistan, his hope for safety was finally fulfilled when he received news that his family would be going to the U.S.

“That day was my birthday,” Saighani said. “I was born renewed.”

Saighani and his family now live in central Arizona. He and his wife are learning English while their children attend school.

His two oldest daughters, who are 15 and 17, are working to complete all four years of high school in one year so they can go to college sooner to provide for their family. They hope to be finished in January next year, and according to Muzhda, they study all day every day to accomplish this goal.

“I know that my daughters will be the heroes of America,” Saighani declared.

Gaining refuge in the U.S. has provided Saighani’s family with the safety and freedom that was stripped from them in Afghanistan, but it has not fully freed him from the terrors of the Taliban.

I just wanted to be safe and not be killed."

Every day, Saighani sees Facebook posts about violence and human rights violations from friends who remain in Afghanistan. With family still in the country, Saighani is restricted from participating in activism for fear they might be killed. However, once his family is safe, he said he wants to speak out again. His primary way of accomplishing this will be through writing.

Between taking care of his family and working as a school janitor, the Afghan writer has several books in the making.

Saighani desires to use his books to expose the truth about the Taliban and enlighten his people. Some of his in-progress works include “The Jail of Women,” referring to the oppression women face in Afghanistan, and “Talking Animals,” about how animals act more civilly than humans.

His biggest desire, though, is to write a book encompassing all that is happening in his home country.

“If I find some supporter here that supports me [a] little, then I have to write everything which is going on in Afghanistan, which will be a very big book,” Saighani said.

Saighani has a long road ahead as he balances his writing, providing for his family and learning English, but he is grateful for all the opportunities he has in the safety of the U.S.

“Every day I go outside and I get a deep breath,” Saighani said, demonstrating with an audible inhale and exhale. “I am so happy that I am here.”

‘We saw people halfway fail, but we succeeded’

Karima Abdullah is a U.S. citizen. Although, unlike most Americans who are born into citizenship, Abdullah’s journey has been years in the making — one that first started almost a decade ago when she fled Afghanistan with her three children.

Abdullah left Afghanistan in 2015 to seek safety and a better life for her family. She lived as a refugee in Pakistan for three years, taking care of her young kids alone as she awaited resettlement.

“Life was much harder [in Pakistan],” Abdullah said — her 19-year-old son translating her Dari to English. “The weather was very hot and you don't have the technology like you have here. You had to work, the kids were still small. It was only me, so I had to do everything.”

After three years in Pakistan, Abdullah’s family was selected for resettlement in Arizona in 2018.

“I was very excited because I wanted to know what I’m going to see, who I’m going to meet, and it’s a different whole world,” Abdullah said.

When she arrived in the U.S., Abdullah was greeted by a case manager from Lutheran Social Services of the Southwest (LSS-SW), one of five resettlement agencies in Arizona.

Once granted resettlement, a refugee’s case is given to a resettlement agency or a sponsor group. When assigned to an agency, a case manager will work with the individual or family from the moment they step off the plane to at least three months after arrival, but often longer according to need.

“Once I got here, the first one or two years was very hard,” Abdullah said. “Then case managers, the [English] teacher and everyone helped to get back my feet so I can keep continuing this journey.”

Through LSS-SW, Abdullah received assistance with housing, getting connected with programs like English learning and employment support, enrolling in public benefits and more.

One of her family’s biggest needs was getting a wheelchair for her oldest child who has cerebral palsy. When Abdullah’s family was in Pakistan and even for a few years in the U.S., her daughter did not have access to a wheelchair and was immobile. However, with the help of their case manager, they recently acquired a wheelchair that can accommodate her daughter’s physical needs and allow her to attend school.

“They always helped us,” Abdullah said. “There's not something they have not done.”

Abdullah has now been in Arizona for six years, and this last year, she gained her U.S. citizenship.

Every refugee who is admitted into the U.S. is put on a path to citizenship, or naturalization. Within one year of entry, they can apply for permanent residence, and after five years, they can apply for citizenship.

The naturalization process consists of an interview and an English and civics test. Abdullah said she studied and went to classes for six months beforehand and passed on her first attempt.

“After that, I went and picked up my son from high school and we went to an Afghan restaurant,” Abdullah said. “It was a very good day.”

Throughout her years in Arizona, Abdullah has worked as an Amazon Flex driver and as her daughter’s caregiver. Through her work, she was able to buy a modest home. Her home has large windows that fill the rooms with light, which she said was especially important as they are a standard in Afghanistan. Her living room is decorated with a blend of American-style furniture, Persian rugs lining the floor and an Afghan sofa set consisting of large floor pillows she made herself.

Abdullah’s two sons have also become citizens and the eldest started college this year. Her daughter is still in the naturalization process as the family works to obtain papers from a doctor to prove her disability and excuse her from the testing. Even as they wait though, the path to citizenship is still clear.

“We moved to America for the safety and refuge for a better life,” Abdullah said. “And just the best part of it is that we succeeded. We saw people halfway fail, but we succeeded.”

‘They'll remember you for their entire life’

In the 2023 fiscal year (FY), the U.S. resettled 60,014 refugees — less than 3% of the worldwide resettlement needs for the year. Arizona welcomed just over 6,000 of these refugees from 44 different countries.

Over the past few years, refugee admissions into the U.S. have been at a record low. According to a 2023 report by the U.S. Refugee Admissions Program, less than 12,000 refugees were resettled in the country in 2021 and less than 30,000 were resettled in 2022. Meanwhile, worldwide refugee numbers have been rising each year.

The refugee admissions ceiling is determined at the start of every FY by the President in consultation with Congress. During Trump’s administration, the ceiling was set as low as 18,000. In the past three years, Biden raised the ceiling to 125,000. The new admissions cap has yet to be reached, but an influx of refugee resettlement is prevalent — agencies like LSS-SW are seeing it firsthand.

In March, case managers and employees at LSS-SW weaved throughout the cubicles and hurried in and out of offices as they described the busyness they were experiencing. For the 2024 FY, the agency is projected to serve 750 refugees, a 66% increase from the prior year.

In 2022, LSS-SW resettled 261 refugees, and in 2023, it resettled 450. By March 20th of this year, it had already received 373 of 750 resettlements.

“Before the COVID, we used to resettle around 1,000,” said Basim Al Khafaji, who is the case management supervisor at LSS-SW. “That will start to pick up again because the whole process when the COVID started was slowed down.”

Resettlement agencies are contracted with the U.S. government to provide initial services to set refugees on a path to self-sufficiency within 90 days.

“That is the goal, that is the goal to get them sufficient,” Al Khafaji said. “Get all their documents, everything set at school for the kids, set them up with medical resources, then jobs.”

The agencies are nonprofit organizations and rely on public and private funding to support their work. The U.S. Reception and Placement (R&P) program provides agencies with a one-time cash or in-kind payment per refugee — LSS-SW receives $1,325 from R&P. This payment is meant to assist with expenses during a refugee’s first three months of resettlement, but depending on the case, the agency may need to supplement with other funding. Al Khafaji said the R&P fund only covers one month of support for an individual, but for a family of ten, it could cover six months.

After the 90-day resettlement period, the agency is then contracted with the state to provide long-term assistance for up to five years after arrival. The services vary depending on needs.

“Anything related to ongoing needs,” Al Khafaji said. “For example, clients got a job, lost a job, want to change job, housing, issues with moving housing, family issues, immigration, we help with obtaining the green card, citizenship, family petitions, so it's an ongoing service.”

Every individual or family is assigned to a case manager who will work directly with them to provide such services. Wilfrida Maseka is one of these case managers who works on the frontline with newcomers.

Maseka, who is a senior case manager, first connected with LSS-SW when she went through its resettlement services as a refugee in 2017.

“Most of us are former refugees, and it's like a sense of giving back to the community cause when we come to the U.S. we receive a lot of help,” Maseka said. “So many people, so many organizations, they come to help you, they welcome you, so you have that sense of debt that you have to pay back to the community.”

Maseka is from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, but she was born in its neighboring country, Rwanda, after her parents left Congo in the ’80s to seek refuge from the crises occurring within its borders. Her parents remained in Rwanda until 1994 when they were forced to go back to Congo after the Rwandan genocide. However, two years later, the First Congo War started between the two countries, leaving Maseka’s family seeking permanent resettlement to escape the violence.

Her family gained refugee status in 1996, but Maseka said they were not considered for resettlement until they made an official request, a detail they were uninformed about for 12 years. Once her family requested resettlement, it took nine more years before they were granted entry into the U.S.

“It was very long cause we got discouraged, you know, we were hoping for so many years, and nothing happened,” Maseka said.

Almost half of the refugees LSS-SW has resettled as of March are Congolese. Nearly seven million people in Congo are displaced and more than one million have sought refuge outside its borders. In 2023, 1,200 refugees from Congo were resettled in Arizona.

“There are so many women here that came from regions where they were tortured, they were abused, stuff like that,” Maseka said. “So, I try to help them with compassion, and I try my best to understand what they're going through, especially speaking the same language with them.”

Maseka has been a case manager for almost two years. She uses her experience as a former refugee to welcome others from her country and its surrounding areas.

“I feel what they're going through; I understand what they're going through,” Maseka said.

In her position, Maseka serves clients who are fluent in one of the 10 languages and dialects she speaks. She assists them with different services to set them on track for self-sufficiency. These services include helping with enrollment in public benefits like food stamps and medical assistance, making home visits to assess ongoing needs and connecting them with LSS-SW programs such as employment support and English learning.

LSS-SW case managers are required to visit their clients twice within the 90-day resettlement period, but Maseka said they often see clients more frequently, sometimes weekly. Reasons for her visits might be to drop off a check for rent, take a client to English classes or help them set up technology, such as getting WhatsApp on their phone.

“Just imagine yourself going somewhere where you can’t talk to anyone, you can’t communicate, you can’t even read, you can’t do anything, you can’t even use the phone,” Maseka said. “It's really tough for them.”

Working as a case manager is difficult, Maseka said, as she deals with many people from different backgrounds and experiences. However, she finds value in providing a space for her clients to express themselves, and she experiences joy in seeing those she has served become successful in the U.S.

“It’s a really important job because we are frontline workers,” Maseka said. “Clients see you when they step foot in the U.S., so you're the first face that they will see in the U.S., and they'll remember you for their entire life.”

‘In our community, no one is doing it like this’

For the past four decades, resettlement agencies have been the primary avenue for assisting incoming refugees in the U.S., but a new path is quickly gaining traction.

In January 2023, a private sponsorship program called Welcome Corps was launched by the U.S. Department of State. Modeled after Canada’s Private Sponsorship of Refugees program, Welcome Corps allows groups of five or more adults to resettle refugees.

Thirteen-thousand sponsor applications have been submitted since the program’s launch. In the first year alone, 15,000 people applied to sponsor over 7,000 refugees.

Among the first refugees to come to the U.S. through Welcome Corps are Ismail Alnasser, Fatin Alfandi and their four children.

Alnasser and Alfandi resettled in Arizona last December. They are originally from Syria — more specifically, they are from the province of Dara’a, where the country’s current conflict broke out.

Syria has been in civil war since 2011. The war ignited after 15 teenagers were arrested and tortured for protesting with graffiti — one of them was killed. This event erupted into more protests followed by the government-sanctioned killing of hundreds of demonstrators and the imprisonment of even more. Conflict has ensued since.

First they used to throw grenades, and then planes were dropping bombs ..."

Alnasser was attending a university in Syria when the war started. He said to go to his classes from home he had to pass 25 checkpoints where he was interrogated by police. One day, while he was walking to class with a friend, he was stopped at a checkpoint and taken to prison after they saw on his ID that he was from Dara’a.

“We were not doing anything; we were walking,” Alnasser said. A translator sat across from him and his wife, translating their Arabic into English.

Alnasser said he was put with 50 other people into a cell no bigger than his current apartment living room. He had no chance to tell his family before he was taken, and he was given no indication as to when he would leave.

“It was a hopeless situation in despair hearing the testimonies of other people being in prison for five months, for a year or so,” Alnasser said. “So, I’m thinking that could have been me. It was, needless to say, a miserable feeling.”

Twenty-five days later, Alnasser had a trial and was released from prison. Soon after, he fled to Jordan, but he returned three months later to finish college. He married his wife, Alfandi, after he went back to Syria. However, conflict persisted and left the couple with no other option but to flee again — this time for good.

“First, they used to throw grenades, and then planes were dropping bombs, so it was a matter of life or death,” Alnasser said.

After they left Syria in 2013, Alnasser and Alfandi’s two-story house was demolished by a bomb, one that destroyed the whole neighborhood.

Their journey back to Jordan took 36 hours. The couple rode in a truck used for transporting animals with 40 people piled inside of it. Smugglers drove them through the desert while avoiding checkpoints along the way.

“It was a very fearful experience because if at any checkpoint [soldiers] saw us, they would shoot at us,” Alfandi said.

The two eventually made it safely to Jordan, where they spent three days in a refugee camp until they found a place of their own. The country ended up becoming their home for the next 10 years, and their four children were born there as refugees.

“When we left Syria to Jordan, we thought we were going to stay for two, three months until the situation calmed down, but of course, the situation got for a year, two, three, up to 10 years,” Alnasser said.

In Jordan, they were safe physically, but they struggled financially. Alnasser said he would take any job he could get, from working in agriculture to painting houses. Before he was able to get a work permit, he said some people tricked him out of payment for jobs he already completed. Without a permit, he was unable to contest.

In 2020, the family was selected to resettle in Europe. However, Alfandi was pregnant at the time with their fourth child, so the resettlement was postponed. The next resettlement was not assigned until three years later, and this time it was not to Europe but to the U.S. There, the family would be welcomed by one of Arizona’s first private sponsor groups.

Alnasser’s family was assigned to a sponsor group under the name International School of Applied Sciences (ISOAS). The group was initiated by former refugee and business owner Phyu Win.

Win’s group is a part of 197 Arizona Welcome Corps applications as of April 1. As a former refugee who came to the U.S. in 2005, when Win saw the news of the program’s launch last year, she knew she had a role to play in it.

“I know what is difficult for all the refugees, new people, coming here,” Win said. “You know, I've been through this kind of stuff, everything.”

Win is from Myanmar, formerly known as Burma — a country that has been plagued by conflict since 1948. Over 2.7 million people are currently displaced within the Southeast Asian country and more than one million have fled its borders for safety.

“To me, in my life, I like to help the refugee people,” Win said. “That is my main important thing, I really want to help.”

Win’s vision with Welcome Corps is to help others from her country. However, because the group initially sponsored when the program was still new, they could not yet select the refugee’s country of origin, so they decided to proceed with a family selected for them. That family was Alnasser, Alfandi and their four young children.

Win’s group welcomed Alnasser’s family in December of last year. The group of nine greeted them at the airport with a big welcome sign and excitement to meet their family.

Private sponsor groups function similarly to resettlement agencies in that they must provide core resettlement services for 90 days after arrival.

ISOAS met with Alnasser’s family almost every day in the beginning to help them with any needs and to acquaint them with the U.S. Within the 90-day resettlement period, the family had already reached the self-sufficiency goal.

However, while the Welcome Corps commitment is 90 days, the sponsor group made their own one-year commitment to the family to continue support.

“We did advise them, you know, the 90 days were coming up,” explained Robert Geirsberg, a member of the sponsor group. “We wanted to make sure they're doing things on their own and that we're thinking about another group, and the first thing out of their mouth was, ‘Don't forget us.’”

Giersberg said he meets with the family almost every other day. As a driving instructor, he is teaching Alfandi how to drive and is training Alnasser to become an instructor.

Alnasser currently has a job putting up awnings, but he said he wants to find another field of work where he can better support his family.

“I dream that I would have my own private work,” Alnasser said. “That I can support my family, something that makes a steady income. Hopefully, in the future, we will be able to buy our own home.”

Alnasser is interested in becoming a barber. However, he is unable to cover school fees and does not have a way to compensate for the working hours he would miss while in school. The sponsor group is working on getting a scholarship for barber school, but in the meantime, Geirsberg is training Alnasser to be an instructional driver so he can have a steady job sooner.

Alnasser has been in Arizona for over five months, and he said life in the U.S. is much better than in Jordan. He said that here his kids have access to college, he can get health insurance and he gets paid for the labor he does. He also hopes to get his citizenship when the time comes.

“In Jordan, we were very much limited,” Alnasser said. “If I left the country, I could not go back, but now as I come here and hopefully get my permanent residency and then citizenship, I can travel anywhere.”

The sponsor group has submitted two more applications since welcoming Alnasser and Alfandi. One application is for refugees Win knows from Myanmar, and the other is for another family selected for them.

There is no end in sight for ISOAS’ work in welcoming and assisting newcomers.

“I want to show myself and all my community also, they can do it,” Win said. “In our community, no one is doing it like this.”

‘I hope she gets everything in this world’

Most refugees come to the U.S. with nothing but their family and a suitcase containing all their worldly possessions. When they leave their countries, many can take little to nothing from their homes, and some flee with only the clothes on their back.

When a resettlement agency welcomes a refugee, it will organize housing and light furnishings for them. However, as a nonprofit, its resources can only stretch so far. This is where the help of The Welcome to America Project (WTAP) comes in.

WTAP is a nonprofit organization located in the Phoenix area that welcomes refugees resettling through an agency by providing them with free resources and items to fill their homes.

“If you've ever met with a refugee or met with somebody who's brand new to America, they have kind of the bare minimum within their household,” said Amela Duric, WTAP’s development manager. “They have, you know, a couch, maybe a bed, one set of bed sheets, just your very bare minimum necessities around their house.”

Throughout the week, WTAP staff do home visits to refugees who are referred by resettlement agencies. They assess the needs of the individual or family, and with volunteers, they begin organizing and packing donated items for delivery. These items may include chairs, kitchen appliances, hygiene products, TVs, bikes and more. Nearly every Saturday, the organization will go with a team of volunteers to welcome families and deliver items. An average of eight families are welcomed each week

The organization also has other programs like bike repair events, free mobile clothing closets and career services.

“The thing about WTAP is we're creating community, and I think it's a beautiful environment for both volunteers and the newcomers,” said Kevin Groman, WTAP’s executive director. “There’s no way to really describe it. It's just a beautiful opportunity.”

Since its creation in 2001, the organization has served over 15,000 refugees from over 40 countries.

“A refugee isn't one face, it isn't one color, it isn't one shape or size,” Duric said. “You don't know someone's story and you don't know where they came from, and that's why it's so important to be empathetic and be kind and be welcoming.”

Duric is a former refugee herself. She came to the U.S. in 1999 when she was seven years old.

Duric was born in Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1992 — the year the Bosnian War broke out. Her parents fled the country when she was only five months old to escape persecution. They left on a bus packed with others who were fleeing and brought only their two children and a bag of clothes, documentation and minimal cash. Duric spent the first seven years of her life moving from different places as her parents sought safety.

“We were living in different refugee housing, and at any given point, you were staying in a room with families of like 30,” Duric said. “So, for me, that was very normal growing up.”

When her family was granted resettlement into the U.S. in ’99, they were assigned to World Relief, a humanitarian organization with resettlement services. A sponsor family with the organization welcomed them at an airport in Illinois and assisted Duric's family throughout their resettlement process.

After their arrival, they were brought to a minimally furnished one-bedroom apartment, which Duric said had about two couches, two twin beds, a TV set on the floor and a few utensils.

Throughout most of her early childhood, Duric never received anything new. When she first arrived in the U.S., she said everything her family received was donated. One of the first new items she was ever given was a pink Razor scooter, still in its box and all for herself.

“I rode that thing that first day like till the wheels fell off,” Duric said. “I think I was all scratched up and I fell off of it like 20 times, but it was mine and mine only, and I was so excited about it.”

Duric moved to Arizona in 2002, and about seven years ago she connected with WTAP as a volunteer. She has been a part of its staff for over a year now.

By working with WTAP, Duric got to relive her childhood memory with her pink scooter through a family she served.

Several years ago, during a Saturday Welcome, Duric visited a Syrian family with three children around the ages of six to nine. While unloading supplies, she noticed a scooter in one of the cars. Duric handed it to one of the daughters, who gazed at the mysterious contraption with confusion. However, once Duric rode the scooter, the little girl was filled with excitement.

“I give it to her and then it hit me, and I was like, ‘Oh my God, that was me,’” Duric said as tears filled her eyes. “I saw myself in her, and it was like, she has no idea what's going on or what's happened or what to expect from life in the next 20 years, but deep down I'm rooting for her, and I'm praying for her and I hope she gets everything in this world.”

The impact of WTAP goes beyond the material items.

Through the organization, some children receive their first-ever gift, parents are given resources to be successful in the U.S., individuals who are welcomed are inspired to serve other newcomers and community is created.

'How much do we have to pay?'

The UNHCR estimated that every year, an average of 385,000 children are born as refugees while their families await protection. Of the 36.4 million refugees in the world right now, over 14 million are children — some who have only known war, never had a home of their own and never experienced safety.

Valencia Newcomer School is a place designed to welcome these children when they start their journey to freedom in Arizona.

Located in the Alhambra Elementary School District in Phoenix, Valencia is a public K-8 school for newcomers to the U.S. who have little to no prior English education. It is the only newcomer school in the state.

“Most of our students are very thankful to be in school,” Lynette Wegner, the school principal, said. “It's so cute, when we're enrolling, so many parents ask us the same question, ‘How much do we have to pay?’ ‘How much is that going to cost us?’ And when I say, ‘It's free, it's for your children, nothing but being a parent and supporting your child, that's all it's gonna cost you.’ The tears, the hugs, the ‘thank you,’ the ‘God bless you’ are amazing.”

The status of a student at Valencia may range from refugee to immigrant or unaccompanied minor. Some of the children have never attended school before, and for some of their parents, their education was a driving factor for coming to the U.S.

Abdullah’s sons were among the first students at Valencia when it opened its gates in 2018, and several of Saighani’s children attended it this year.

Before Valencia opened six years ago, refugee and immigrant children in the Phoenix area were mostly placed in general education classrooms, where many struggled for years to reclassify out of the English Learner (EL) program. Wegner was an academic coach in the Alhambra district and said she witnessed various teachers struggle to support newcomer students.

“[We] saw kids coloring, a lot of coloring, a lot of tracing, not really being taught, just kind of pushed to the side because [teachers] just didn't know what to do with them,” Wegner said. “A lot of crying, running out of the classroom, a lot of chasing.”

Children who went through strenuous journeys to come to the U.S. did not understand that they were not being taken from their parents forever when they were dropped off on campus. Kids who came from war-torn countries where planes regularly dropped bombs were left in utter fear when aircraft flew over the school, and when school alarms sounded for drills, they experienced nothing but terror.

“Try to experience a lockdown in a public school with kids that have just come from Afghanistan,” Wegner said. “It's just traumatizing.”

In 2017, Wegner was assigned to a task force that studied newcomer schools across the country to find a way to support refugee and immigrant children who were struggling in the district’s public schools. That task force paved the way for Valencia’s opening in 2018. When the school was established, Wegner was placed as its director, a title that later changed to principal.

Since day one, Wegner has made it a priority for students to feel welcomed at school. Every morning, the staff greets students at the gates and at classroom doors with hugs, high fives and smiles as upbeat music plays across campus.

“The expectation of greeting children when they first come on campus, whatever that looks like, it needs to happen,” Wegner said. “Greeting them at the door, letting them know that we are so happy you are here to learn. And so, we want that, we want them to come back, we want them to know that school is a safe and happy place to learn.”

Over 18 countries are represented in all the students who currently attend Valencia, and a blend of 12 languages is spoken by them. Over 350 students have cycled through the school this year and 162 currently attend.

Most of our students are very thankful to be in school."

The school’s goal is to get students ready to attend their zoned public school within one year of arrival. During class time, teachers implement English language learning into lessons and build up to grade-level content in standard school subjects like math and science.

While Valencia works to get students acclimated to the U.S. education system, it also plays a role in introducing them to a new way of life.

“I have kids that if we were to let them, they would wear the same clothes every day because that's all they had,” Priscilla Varela, the school’s counselor and social worker, said. “They are happy to be here, and they don't care what they wear as long as they're here, obtaining their education and getting a meal.”

The students at Valencia come from many different backgrounds. Some may have spent countless days traveling through jungles or deserts trying to come to the U.S., some have lost family members on their journeys and some have lived their entire young lives in refugee camps.

“I had a couple of kiddos from Rwanda, who had to walk like 10 miles one way to get to school,” Varela said. “So for them, getting on the bus is super exciting because they get brought to school.”

Valencia has several resources and programs to support students and families outside of the classroom.

In her role as a counselor and social worker, Varela will often make home visits to families to provide resources and services. She has done visits to deliver food boxes, hygiene kits, bus passes and more.

Students get free breakfast and lunch daily, and once a month, families can pick up fresh fruits and vegetables at the school through a program called Brighter Bites. Valencia also has a free clothing closet filled with shirts, shoes, jackets, diapers, hygiene products and more that students and their families can access during school hours. Three times a year, WTAP comes to the school’s campus to host additional clothing closets for all families.

“I want every one of our families to know that school is not just for their children's education, but it's a safe place to go to get help,” Wegner said. “We have a lot of families that just come here needing help.”

A letter to Americans

— Written by Baba Jan Saighani

I thank you because you helped me. You worked and paid taxes, and with your tax money, the American government was able to save me from the threat of death and bring me here.

You put your extra household items next to this garbage can. And several times I got household items from this garbage for free and took them to my house and solved my problem. While you don’t know that you helped me unintentionally, I am writing right now on the desk I got from your help.

I am indebted to you, and I hope that I can serve here in the future and repay your services.

Post a comment